title: TS(TypeScript)看这篇就够了

date: 2024-04-23 15:48:28.352

updated: 2024-04-30 10:24:27.118

url: https://blog.huangge1199.cn/archives/tstypescript-kan-zhe-pian-jiu-gou-le

categories:

- 前端

tags: 前端

Typescript 简介

TypeScript是用于应用程序规模开发的JavaScript。

TypeScript是强类型,面向对象的编译语言。它是由微软的Anders Hejlsberg(C#的设计者)设计的。

TypeScript既是一种语言又是一组工具。TypeScript是JavaScript的一个超集。换句话说,TypeScript是JavaScript加上一些额外的功能。

TypeScript 扩展了 JavaScript 的语法,所以任何现有的 JavaScript 程序可以不加改变的在 TypeScript 下工作。TypeScript 是为大型应用之开发而设计,而编译时它产生 JavaScript 以确保兼容性。

TypeScript 可以编译出纯净、 简洁的 JavaScript 代码,并且可以运行在任何浏览器上、Node.js 环境中和任何支持 ECMAScript 3(或更高版本)的 JavaScript 引擎中。

TypeScript 的优势

TypeScript相对于纯粹的JavaScript具有许多优势,特别是在开发大型应用程序时。以下是一些TypeScript的优势:

静态类型系统

TypeScript引入了静态类型系统,允许开发者在声明变量、函数参数、返回值等时指定类型。这种静态类型检查可以帮助捕获常见的编程错误,例如类型不匹配、未定义的属性或方法等,提供更好的代码质量和可靠性。

更好的代码智能感知

因为TypeScript了解代码中的类型信息,因此编辑器可以提供更准确和强大的代码智能感知和自动补全功能。这可以显著提高开发效率,并减少常见的编码错误。

更易于重构和维护

静态类型和面向对象特性使得代码更模块化、更结构化,从而更易于重构和维护。IDE可以更好地支持重构操作,并能够更好地理解代码的结构和依赖关系。

更丰富的面向对象特性

TypeScript支持类、接口、继承、多态等面向对象编程的特性,使得代码组织更清晰、更易于理解。这对于构建大型应用程序非常有用。

更好的工具支持:

TypeScript配合现代的集成开发环境(如VS Code、WebStorm等),可以提供强大的代码导航、重构、调试和代码分析工具。此外,TypeScript还能够与许多流行的前端框架(如Angular、React等)良好集成。

增强的语言功能:

TypeScript不仅仅是JavaScript的超集,它还引入了一些新的语言功能,如箭头函数、可选参数、默认参数、模板字符串等,使得代码更简洁和易读。

更好的生态系统:

TypeScript拥有庞大的社区支持,许多常用的JavaScript库和框架都提供了类型定义文件,可以轻松地与TypeScript集成。这使得使用第三方库时具有更好的类型安全性和开发体验。

基础类型

TypeScript支持与JavaScript几乎相同的数据类型 数字,字符串,结构体,布尔值等,此外还提供了实用的枚举类型方便我们使用。

布尔值

最基本的数据类型就是简单的 true/false 值,在 JavaScript 和 TypeScript 里叫做 boolean(其它语言中也一样)。 我们来定义一个布尔类型的变量:

let isDone: boolean = false;

在TypeScript中, 在参数名称后面使用冒号:来指定参数的类型

let 变量名: 数据类型

数字

和 JavaScript 一样,TypeScript 里的所有数字都是浮点数。 这些浮点数的类型是 number。 除了支持十进制和十六进制字面量,TypeScript 还支持 ECMAScript 2015 中引入的二进制和八进制字面量。

let decLiteral: number = 6;

let hexLiteral: number = 0xf00d;

let binaryLiteral: number = 0b1010;

let octalLiteral: number = 0o744;

字符串

字符串新特性

JavaScript 程序的另一项基本操作是处理网页或服务器端的文本数据。 像其它语言里一样,我们使用 string 表示文本数据类型。 和 JavaScript 一样,可以使用双引号 “或单引号'表示字符串。

let name: string = "bob";

name = "loen";

以上字符串不支持换行.

多行字符串

在Typescript中你可以使用反引号 ` 表示多行字符串.

let hello: string = `Welcome to

W3cschool`;

内嵌表达式

你还可以使用模版字符串,也就是在反引号中使用 ${ expr }这种形式嵌入表达式

let name: string = `Loen`;

let age: number = 37;

let sentence: string = `Hello, my name is ${ name }.

I'll be ${ age + 1 } years old next month.`;

这与下面定义sentence的方式效果相同:

let sentence: string = "Hello, my name is " + name + ".\n\n" +

"I'll be " + (age + 1) + " years old next month.";

我们可以看到Typescript定义的字符串更加清晰简单.

自动拆分字符串

我们可以用字符串模板去调用一个方法

function userinfo(params,name,age){

console.log(params);

console.log(name);

console.log(age);

}

let myname = "Loen Wang";

let getAge = function(){

return 18;

}

// 调用

userinfo`hello my name is ${myname}, i'm ${getAge()}`

结果:

-kan-zhe-pian-jiu-gou-le/2024-04-23-16-18-22-image.png)

数组

TypeScript 有两种方式可以定义数组。

第一种, 是在元素类型后面接上 [],表示由此类型元素组成的一个数组:

let list: number[] = [1, 2, 3];

第二种方式是使用数组泛型,Array<元素类型>:

let list: Array<number> = [1, 2, 3];

元组 Tuple

元组类型允许表示一个已知元素数量和类型的数组,各元素的类型不必相同。 比如,你可以定义一对值分别为 string 和 number 类型的元组。

// 声明一个元组类型

let x: [string, number];

// 初始化元组

x = ['hello', 10];

x = [10, 'hello']; // 这里会报错,类型错误

枚举

enum 类型是对 JavaScript 标准数据类型的一个补充。 像 C# 等其它语言一样,使用枚举类型可以为一组数值赋予友好的名字。

enum Color {Red, Green, Blue}

let c: Color = Color.Green;

默认情况下,从0开始为元素编号。 你也可以手动的指定成员的数值。 例如,我们将上面的例子改成从 1开始编号:

enum Color {Red = 1, Green, Blue}

let c: Color = Color.Green;

或者,全部都采用手动赋值:

enum Color {Red = 1, Green = 2, Blue = 4}

let c: Color = Color.Green;

枚举类型提供的一个便利是你可以由枚举的值得到它的名字。 例如,我们知道数值为2,但是不确定它映射到Color里的哪个名字,我们可以查找相应的名字:

enum Color {Red = 1, Green, Blue}

let colorName: string = Color[2];

alert(colorName); // 显示'Green'因为上面代码里它的值是2

Any

如果不希望类型检查器对值进行检查,直接通过编译阶段的检查。 那么我们可以使用 any类型来标记这些变量:

let notSure: any = 4;

notSure = "这是一个字符串";

notSure = false; // 现在我们又可以将其改成布尔类型

在对现有代码进行改写的时候,any类型是十分有用的,它允许你在编译时可选择地包含或移除类型检查。 你可能认为 Object有相似的作用,就像它在其它语言中那样。 但是 Object类型的变量只是允许你给它赋任意值 - 但是却不能够在它上面调用任意的方法,即便它真的有这些方法:

let notSure: any = 4;

notSure.ifItExists();// 存在这个方法

notSure.toFixed(); // 存在这个方法

let prettySure: Object = 4;

prettySure.toFixed(); // 错误:对象类型上不存在 toFixed 属性

当你只知道一部分数据的类型时,any类型也是有用的。 比如,你有一个数组,它包含了不同的类型的数据:

let list: any[] = [1, true, "free"];

list[1] = 100;

Void

某种程度上来说,void类型像是与any类型相反,它表示没有任何类型。 当一个函数没有返回值时,你通常会见到其返回值类型是 void:

function warnUser(): void {

alert("This is my warning message");

}

声明一个void类型的变量没有什么大用,因为你只能为它赋予undefined和null:

let unusable: void = undefined;

Null 和 Undefined

TypeScript 里,undefined 和 null 两者各自有自己的类型分别叫做 undefined 和 null。 和 void 相似,它们的本身的类型用处不是很大:

// 我们无法给这些变量赋值

let u: undefined = undefined;

let n: null = null;

默认情况下 null 和 undefined 是所有类型的子类型。

就是说你可以把 null 和 undefined 赋值给 number 类型的变量。

然而,当你编译时指定了 –strictNullChecks 标记, null 和 undefined 只能赋值给 void 和它们自己。

注意:我们鼓励尽可能地使用

--strictNullChecks,但在本教程里我们假设这个标记是关闭的。

Never

never 类型表示的是那些永不存在的值的类型。

例如, never 类型是那些总是会抛出异常或根本就不会有返回值的函数表达式或箭头函数表达式的返回值类型;

never 类型是任何类型的子类型,也可以赋值给任何类型; 然而,没有类型是 never 的子类型或可以赋值给 never 类型(除了 never 本身之外)。 即使 any 也不可以赋值给 never 。

下面是一些返回 never 类型的函数:

// 返回never的函数必须存在无法达到的终点

function error(message: string): never {

throw new Error(message);

}

// 推断的返回值类型为never

function fail() {

return error("Something failed");

}

// 返回never的函数必须存在无法达到的终点

function infiniteLoop(): never {

while (true) {

}

}

箭头表达式将再后面的课程中学习到。

类型断言

通过类型断言这种方式可以告诉编译器,“相信我,我知道自己在干什么”。 类型断言好比其它语言里的类型转换,但是不进行特殊的数据检查和解构。 它没有运行时的影响,只是在编译阶段起作用。

TypeScript 会假设你,程序员,已经进行了必须的检查。

类型断言有两种形式。 其一是尖括号语法:

let someValue: any = "this is a string";

let strLength: number = (<string>someValue).length;

另一个为as语法:

let someValue: any = "this is a string";

let strLength: number = (someValue as string).length;

两种形式是等价的。 至于使用哪个大多数情况下是凭个人喜好;

然而,当你在 TypeScript 里使用 JSX 时,只有 as语法断言是被允许的。

符号介绍

自ECMAScript 2015起,symbol成为了一种新的原生类型,就像number和string一样。

symbol类型的值是通过Symbol构造函数创建的。

let sym1 = Symbol();

let sym2 = Symbol("key"); // 可选的字符串key

Symbols是不可改变且唯一的。

let sym2 = Symbol("key");

let sym3 = Symbol("key");

sym2 === sym3; // false

symbols是唯一的像字符串一样,symbols也可以被用做对象属性的键。

let sym = Symbol();

let obj = {

[sym]: "value"

};

console.log(obj[sym]); // "value"

Symbols也可以与计算出的属性名声明相结合来声明对象的属性和类成员。

const getClassNameSymbol = Symbol();

class C {

[getClassNameSymbol](){

return "C";

}

}

let c = new C();

let className = c[getClassNameSymbol](); // "C"

变量声明

let和const

let和const是JavaScript里相对较新的变量声明方式。 像我们之前提到过的, let在很多方面与var是相似的,但是可以帮助大家避免在JavaScript里常见一些问题。 const只能一次赋值, 再次赋值会报错。

- let可以多次写入

- const只允许一次写入

因为 TypeScript 是 JavaScript 的超集,所以它本身就支持let和const。 下面我们会详细说明这些新的声明方式以及为什么推荐使用它们来代替 var。

var 声明

一直以来我们都是通过var关键字定义 JavaScript 变量。

var a = 10;

大家都能理解,这里定义了一个名为a值为10的变量。

我们也可以在函数内部定义变量:

function f() {

var message = "Hello, world!";

return message;

}

并且我们也可以在其它函数内部访问相同的变量。

function f() {

var a = 10;

return function g() {

var b = a + 1;

return b;

}

}

var g = f();

g(); // returns 11;

上面的例子里,g 可以获取到 f 函数里定义的 a 变量。 每当 g 被调用时,它都可以访问到 f 里的 a 变量。 即使当 g 在 f 已经执行完后才被调用,它仍然可以访问及修改 a 。

function f() {

var a = 1;

a = 2;

var b = g();

a = 3;

return b;

function g() {

return a;

}

}

f(); // returns 2

作用域规则

对于熟悉其它语言的人来说,var声明有些奇怪的作用域规则。 看下面的例子:

function f(shouldInitialize: boolean) {

if (shouldInitialize) {

var x = 10;

}

return x;

}

f(true); // returns '10'

f(false); // returns 'undefined'

变量 x 是定义在 if 语句里面 ,但是我们却可以在语句的外面访问它。 这是因为 var声明可以在包含它的函数,模块,命名空间或全局作用域内部任何位置被访问,包含它的代码块对此没有什么影响。

这些作用域规则可能会引发一些错误。 其中之一就是,多次声明同一个变量并不会报错:

function sumMatrix(matrix: number[][]) {

var sum = 0;

for (var i = 0; i < matrix.length; i++) {

var currentRow = matrix[i];

for (var i = 0; i < currentRow.length; i++) {

sum += currentRow[i];

}

}

return sum;

}

这里很容易看出一些问题,里层的 for 循环会覆盖变量 i,因为所有 i 都引用相同的函数作用域内的变量。 这很容易引发无穷的麻烦。

let 声明

现在你已经知道了var存在一些问题,这恰好说明了为什么用let语句来声明变量。

let hello = "Hello!";

块作用域

当用 let 声明一个变量,它使用的是词法作用域或块作用域。 不同于使用 var 声明的变量那样可以在包含它们的函数外访问,块作用域变量在包含它们的块或 for 循环之外是不能访问的。

function f(input: boolean) {

let a = 100;

if (input) {

// Still okay to reference 'a'

let b = a + 1;

return b;

}

// Error: 'b' doesn't exist here

return b;

}

这里我们定义了2个变量 a 和 b 。 a 的作用域是 f 函数体内,而 b 的作用域是 if 语句块里。

在catch语句里声明的变量也具有同样的作用域规则。

try {

throw "oh no!";

}

catch (e) {

console.log("Oh well.");

}

// Error: 'e' doesn't exist here

console.log(e);

拥有块级作用域的变量的另一个特点是,它们不能在被声明之前读或写。

虽然这些变量始终“存在”于它们的作用域里,但在直到声明它的代码之前的区域都属于 暂时性死区。 它只是用来说明我们不能在 let语句之前访问它们,幸运的是 TypeScript 可以告诉我们这些信息。

a++; // illegal to use 'a' before it's declared;

let a;

注意: 我们仍然可以在一个拥有块作用域变量被声明前获取它。 只是我们不能在变量声明前去调用那个函数。 如果生成代码目标为ES2015,现代的运行时会抛出一个错误;然而,现今 TypeScript 是不会报错的。

function foo() {

// okay to capture 'a'

return a;

}

// 不能在'a'被声明前调用'foo'

// 运行时应该抛出错误

foo();

let a;

重定义及屏蔽

我们提过使用 var 声明时,它不在乎你声明多少次;你只会得到1个。

function f(x) {

var x;

var x;

if (true) {

var x;

}

}

在上面的例子里,所有x的声明实际上都引用一个相同的x,并且这是完全有效的代码。 这经常会成为bug的来源。 好的是, let声明就不会这么宽松了。

let x = 10;

let x = 20; // 错误,不能在1个作用域里多次声明`x`

并不是要求两个均是块级作用域的声明 TypeScript 才会给出一个错误的警告。

function f(x) {

let x = 100; // error: interferes with parameter declaration

}

function g() {

let x = 100;

var x = 100; // 错误:不能同时声明'x'

}

并不是说块级作用域变量不能用函数作用域变量来声明。 而是块级作用域变量需要在明显不同的块里声明。

function f(condition, x) {

if (condition) {

let x = 100;

return x;

}

return x;

}

f(false, 0); // returns 0

f(true, 0); // returns 100

在一个嵌套作用域里引入一个新名字的行为称做屏蔽。 它是一把双刃剑,它可能会不小心地引入新问题,同时也可能会解决一些错误。 例如,假设我们现在用 let重写之前的sumMatrix函数。

function sumMatrix(matrix: number[][]) {

let sum = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < matrix.length; i++) {

var currentRow = matrix[i];

for (let i = 0; i < currentRow.length; i++) {

sum += currentRow[i];

}

}

return sum;

}

这个版本的循环能得到正确的结果,因为内层循环的i可以屏蔽掉外层循环的i。

通常来讲应该避免使用这种屏蔽,因为我们需要写出清晰的代码。

块级作用域变量的获取

let声明每次迭代都会创建一个新作用域。 这就是我们在使用立即执行的函数表达式时做的事,所以在 setTimeout 例子里我们仅使用 let 声明就可以了。

for (let i = 0; i < 10 ; i++) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i);

}, 100 * i);

}

会输出与预料一致的结果:

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

const 声明

const 声明是声明变量的另一种方式。

const numLivesForCat = 9;

const声明的变量只允许一次赋值, 引用的值是不可变的。

const numLivesForCat = 9;

const kitty = {

name: "Aurora",

numLives: numLivesForCat,

}

// 重新赋值一个类会报错

kitty = {

name: "Loen",

numLives: numLivesForCat

};

// 属性修改是允许的

kitty.name = "Rory";

kitty.name = "Kitty";

kitty.name = "Cat";

kitty.numLives--;

除非你使用特殊的方法去避免,实际上const变量的内部状态是可修改的。 幸运的是,TypeScript允许你将对象的成员设置成只读的。

解构

解构数组

最简单的解构莫过于数组的解构赋值了:

let input = [1, 2];

let [first, second] = input;

console.log(first); // outputs 1

console.log(second); // outputs 2

这创建了2个命名变量 first 和 second。 相当于使用了索引,但更为方便:

first = input[0];

second = input[1];

解构作用于已声明的变量会更好:

// 对换变量的值

[first, second] = [second, first];

作用于函数参数:

function f([first, second]: [number, number]) {

console.log(first);

console.log(second);

}

f(input);

你可以在数组里使用...语法创建剩余变量:

let [first, ...rest] = [1, 2, 3, 4];

console.log(first); // outputs 1

console.log(rest); // outputs [ 2, 3, 4 ]

当然,由于是 JavaScript, 你可以忽略你不关心的尾随元素:

let [first] = [1, 2, 3, 4];

console.log(first); // outputs 1

或其它元素:

let [, second, , fourth] = [1, 2, 3, 4];

对象解构

你也可以解构对象:

let o = {

a: "foo",

b: 12,

c: "bar"

};

let { a, b } = o;

这通过 o.a and o.b 创建了 a 和 b 。 注意,如果你不需要 c 你可以忽略它。

就像数组解构,你可以用没有声明的赋值:

({ a, b } = { a: "baz", b: 101 });

注意:我们需要用括号将它括起来,因为Javascript通常会将以 { 起始的语句解析为一个块。

你可以在对象里使用…语法创建剩余变量:

let { a, ...passthrough } = o;

let total = passthrough.b + passthrough.c.length;

属性重命名

你也可以给属性以不同的名字:

let { a: newName1, b: newName2 } = o;

这里的语法开始变得混乱。 你可以将 a: newName1 读做 a 作为 newName1。 方向是从左到右,好像你写成了以下样子:

let newName1 = o.a;

let newName2 = o.b;

令人困惑的是,这里的冒号不是指示类型的。 如果你想指定它的类型, 仍然需要在其后写上完整的模式。

let {a, b}: {a: string, b: number} = o;

默认值

默认值可以让你在属性为 undefined 时使用缺省值:

function keepWholeObject(wholeObject: { a: string, b?: number })

{

let { a, b = 1001 } = wholeObject;

}

现在,即使 b 为 undefined , keepWholeObject 函数的变量 wholeObject 的属性 a 和 b 都会有值。

函数声明

解构也能用于函数声明。 看以下简单的情况:

type C = { a: string, b?: number }

function f({ a, b }: C): void {

// ...

}

通常情况下更多的是指定默认值,解构默认值有些棘手。 首先,你需要在默认值之前设置其格式。

function f({ a, b } = { a: "", b: 0 }): void {

// ...

}

f(); // 默认 { a: "", b: 0 }

你需要知道在解构属性上给予一个默认或可选的属性用来替换主初始化列表。 要知道 C 的定义有一个 b 可选属性:

function f({ a, b = 0 } = { a: "" }): void {

// ...

}

f({ a: "yes" }); // 默认 b = 0

f(); // 默认 {a: ""}, b = 0

f({}); // 错误, 如果您提供参数,则需要'a'

从前面的例子可以看出, 要小心使用解构。就算是最简单的解构表达式也是难以理解的。 尤其当存在深层嵌套解构的时候,就算这时没有堆叠在一起的重命名,默认值和类型注解,也是令人难以理解的。

解构表达式要尽量保持小而简单。

展开

展开操作符正与解构相反。 它允许你将一个数组展开为另一个数组,或将一个对象展开为另一个对象。 例如:

let first = [1, 2];

let second = [3, 4];

let bothPlus = [0, ...first, ...second, 5];

这会令bothPlus的值为 [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] 。 展开操作创建了 first 和 second 的一份浅拷贝。 它们不会被展开操作所改变。

你还可以展开对象:

let defaults = { food: "spicy", price: "$", ambiance: "noisy" };

let search = { ...defaults, food: "rich" };

search的值为 { food: “rich”, price: “$“, ambiance: “noisy” } 。 对象的展开比数组的展开要复杂的多。 像数组展开一样,它是从左至右进行处理,但结果仍为对象。 这就意味着出现在展开对象后面的属性会覆盖前面的属性。 因此,如果我们修改上面的例子,在结尾处进行展开的话:

let defaults = { food: "spicy", price: "$", ambiance: "noisy" };

let search = { food: "rich", ...defaults };

那么, defaults 里的 food 属性会重写 food: “rich” ,在这里这并不是我们想要的结果。

对象展开还有其它一些意想不到的限制。 首先,它仅包含对象 自身的可枚举属性。 大体上是说当你展开一个对象实例时,你会丢失其方法:

class C {

p = 12;

m() {

}

}

let c = new C();

let clone = { ...c };

clone.p; // 没问题

clone.m(); // 错误

函数

函数介绍

函数是JavaScript应用程序的基础。 它帮助你实现抽象层,模拟类,信息隐藏和模块。 在TypeScript里,虽然已经支持类,命名空间和模块,但函数仍然是主要的定义 行为的地方。 TypeScript为JavaScript函数添加了额外的功能,让我们可以更容易地使用。

Typescript 函数

和JavaScript一样,TypeScript函数可以创建有名字的函数和匿名函数。 你可以随意选择适合应用程序的方式,不论是定义一系列API函数还是只使用一次的函数。

通过下面的例子可以迅速回想起这两种JavaScript中的函数:

// 命名函数

function add(x, y) {

return x + y;

}

// 匿名函数

let myAdd = function(x, y) { return x + y; };

函数类型

为函数定义类型 我们可以为函数本身添加返回值类型。

函数():类型 {}

我们给函数添加类型:

function add(x: number, y: number): number {

return x + y;

}

let myAdd = function(x: number, y: number): number { return x + y; };

TypeScript能够根据返回语句自动推断出返回值类型,因此我们通常省略它。

函数参数

TypeScript里的每个函数参数都是必须的。 传递给一个函数的参数个数必须与函数期望的参数个数一致。

function buildName(firstName: string, lastName: string) {

return firstName + " " + lastName;

}

// error, too few parameters

let result1 = buildName("Bob");

// error, too many parameters

let result2 = buildName("Bob", "Adams", "Sr.");

// 这种方式是正确的

let result3 = buildName("Bob", "Adams");

可选参数

在TypeScript里我们可以在参数名旁使用 ? 实现可选参数的功能。 比如,我们想让last name是可选的:

function buildName(firstName: string, lastName?: string) {

if (lastName)

return firstName + " " + lastName;

else

return firstName;

}

// 现在这样也可以

let result1 = buildName("Bob");

// error, too many parameters

let result2 = buildName("Bob", "Adams", "Sr.");

// 这种方式是正确的

let result3 = buildName("Bob", "Adams");

注意: 可选参数必须跟在必须参数后面。 如果上例我们想让first name是可选的,那么就必须调整它们的位置,把first name放在后面。

默认参数

在TypeScript里,我们也可以为参数提供一个默认值。让我们修改上例,把last name的默认值设置为"Smith”。

function buildName(firstName: string, lastName = "Smith") {

return firstName + " " + lastName;

}

// 这样是可以工作的 返回 "Bob Smith"

let result1 = buildName("Bob");

// 这样也可以工作返回 "Bob Smith"

let result2 = buildName("Bob", undefined);

// error, too many parameters

let result3 = buildName("Bob", "Adams", "Sr.");

// 这是正确的返回 "Bob Adams"

let result4 = buildName("Bob", "Adams");

剩余参数

当你想同时操作多个参数,而你并不知道会有多少参数传递进来。 在JavaScript里,你可以使用 arguments来访问所有传入的参数。 而在TypeScript里,你可以使用 …变量名 把所有参数收集到一个变量里:

function buildName(firstName: string, ...restOfName: string[]) {

return firstName + " " + restOfName.join(" ");

}

let employeeName = buildName("Joseph", "Samuel", "Lucas", "MacKinzie");

剩余参数会被当做个数不限的可选参数。 可以一个都没有,同样也可以有任意个。

这个省略号也会在带有剩余参数的函数类型定义上使用到:

function buildName(firstName: string, ...restOfName: string[]) {

return firstName + " " + restOfName.join(" ");

}

箭头函数

表现形式

基本语法 ES6 允许使用“箭头”(=>)定义函数 箭头函数相当于匿名函数,并且简化了函数定义 表现形式一: 包含一个表达式,连{ … }和return都省略掉了

x => x * x

//等同于

function (x) {

return x*x;

};

表示形式二: 包含多条语句,这时候就不能省略{ … }和return

x => {

if (x > 0) {

return x * x;

}

else {

return - x * x;

}

}

this

箭头函数的引入有两个方面的作用:

- 一是更简短的函数书写

- 二是对this的词法解析。

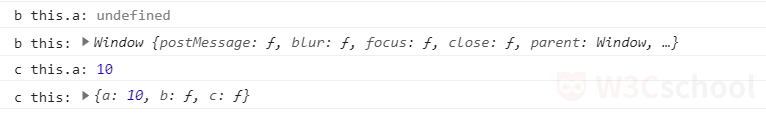

普通函数: this指向调用它的那个对象 箭头函数:不绑定this,会捕获其所在的上下文的this值,作为自己的this值,任何方法都改变不了其指向,如: call(),bind(),apply()

var obj = {

a: 10,

b: () => {

console.log('b this.a:',this.a); // undefined

console.log('b this:',this); // Window

},

c: function() {

console.log('c this.a:',this.a); // 10

console.log('c this:',this); // {a: 10, b: ƒ, c: ƒ}

}

}

obj.b();

obj.c();

执行结果:

函数重载

所谓函数重载就是同一个函数,根据传递的参数不同,会有不同的表现形式。

JavaScript本身是没有重载这个概念,不过可以模拟实现。 JavaScript 代码实例如下:

function func(){

if(arguments.length==0){

alert("欢迎来到w3cschool");

}

else if(arguments.length==1){

alert(arguments[0])

}

}

func();

func(2);

上面代码利用arguments对象来判断传递参数的数量,然后执行不同的代码。

TypeScript 函数重载

TypeScript提供了重载功能,TypeScript的函数重载只有一个函数体,也就是说无论声明多少个同名且不同签名的函数,它们共享一个函数体,在调用时会根据传递实参类型的不同,利用流程控制语句控制代码的执行。

TypeScript代码实例如下:

function func(x:string):string;

function func(x:number):number;

function func(x:any):any{

if(typeof x=="string"){

return "欢迎来到w3cschool"

}else if(typeof x=="number"){

return 5

}

}

function func(x:any):any不是函数重载列表一部分,所以上述代码只定义两个重载。

重载函数的共用函数体部分如下:

function func(x:any):any{

if(typeof x=="string"){

return "欢迎来到w3cschool"

}else if(typeof x=="number"){

return 5

}

}

重载函数编译后的JavaScript代码:

function func(x) {

if (typeof x == "string") {

return "欢迎来到w3cschool";

}

else if (typeof x == "number") {

return 5;

}

}

由于JavaScript本身不支持重载,所以TypeScript重载实质上为了方便调用者如何调用函数。

接口

接口介绍

在TypeScript里,接口的作用就是为这些类型命名和为你的代码或第三方代码定义契约。

接口初探

下面通过一个简单示例来观察接口是如何工作的:

function printLabel(labelledObj: { label: string }) {

console.log(labelledObj.label);

}

let myObj = { size: 10, label: "Size 10 Object" };

printLabel(myObj);

类型检查器会查看 printLabel 的调用。 printLabel 有一个参数,并要求这个对象参数有一个名为 label 类型为 string 的属性。

需要注意的是,我们传入的对象参数实际上会包含很多属性,但是编译器只会检查那些必需的属性是否存在,并且其类型是否匹配。

下面我们重写上面的例子,这次使用接口来描述:必须包含一个 label 属性且类型为 string :

interface LabelledValue {

label: string;

}

function printLabel(labelledObj: LabelledValue) {

console.log(labelledObj.label);

}

let myObj = {size: 10, label: "Size 10 Object"};

printLabel(myObj);

LabelledValue接口就好比一个名字,用来描述上面例子里的要求。 它代表了有一个 label 属性且类型为 string 的对象。

只要传入的对象满足上面提到的必要条件,那么它就是被允许的。

类型检查器不会去检查属性的顺序,只要相应的属性存在并且类型也是对的就可以。

可选属性

接口里的属性不全都是必需的。 有些是只在某些条件下存在,或者根本不存在。 可选属性在应用“option bags”模式时很常用,即给函数传入的参数对象中只有部分属性赋值了。

下面是应用了“option bags”的例子:

interface SquareConfig {

color?: string;

width?: number;

}

function createSquare(config: SquareConfig): {color: string; area: number} {

let newSquare = {color: "white", area: 100};

if (config.color) {

newSquare.color = config.color;

}

if (config.width) {

newSquare.area = config.width * config.width;

}

return newSquare;

}

let mySquare = createSquare({color: "black"});

带有可选属性的接口与普通的接口定义差不多,只是在可选属性名字定义的后面加一个?符号。

可选属性的好处之一是可以对可能存在的属性进行预定义,好处之二是可以捕获引用了不存在的属性时的错误。 比如,我们故意将 createSquare里的color属性名拼错,就会得到一个错误提示:

interface SquareConfig {

color?: string;

width?: number;

}

function createSquare(config: SquareConfig): { color: string; area: number } {

let newSquare = {color: "white", area: 100};

if (config.color) {

// Error: Property 'clor' does not exist on type 'SquareConfig'

newSquare.color = config.clor;

}

if (config.width) {

newSquare.area = config.width * config.width;

}

return newSquare;

}

let mySquare = createSquare({color: "black"});

只读属性

可以在属性名前用 readonly来指定只读属性:

interface Point {

readonly x: number;

readonly y: number;

}

可以通过赋值一个对象字面量来构造一个Point。 赋值后, x 和 y 再也不能被改变了。

let p1: Point = { x: 10, y: 20 };

p1.x = 5; // error!

TypeScript 具有 ReadonlyArray

let a: number[] = [1, 2, 3, 4];

let ro: ReadonlyArray<number> = a;

ro[0] = 12; // error!

ro.push(5); // error!

ro.length = 100; // error!

a = ro; // error!

上面代码的最后一行,可以看到就算把整个ReadonlyArray赋值到一个普通数组也是不可以的。 但是你可以用类型断言重写:

a = ro as number[];

readonly, const使用时机

做为变量使用的话用 const ,若做为属性则使用 readonly 。

函数类型

接口能够描述JavaScript中对象拥有的各种各样的外形。 除了描述带有属性的普通对象外,接口也可以描述函数类型。

为了使用接口表示函数类型,我们需要给接口定义一个调用签名。 它就像是一个只有参数列表和返回值类型的函数定义。参数列表里的每个参数都需要名字和类型。

interface SearchFunc {

(source: string, subString: string): boolean;

}

这样定义后,我们可以像使用其它接口一样使用这个函数类型的接口。 下例展示了如何创建一个函数类型的变量,并将一个同类型的函数赋值给这个变量。

let mySearch: SearchFunc;

mySearch = function(source: string, subString: string) {

let result = source.search(subString);

return result > -1;

}

对于函数类型的类型检查来说,函数的参数名不需要与接口里定义的名字相匹配。 比如,我们使用下面的代码重写上面的例子:

let mySearch: SearchFunc;

mySearch = function(src: string, sub: string): boolean {

let result = src.search(sub);

return result > -1;

}

函数的参数会逐个进行检查,要求对应位置上的参数类型是兼容的。 如果你不想指定类型,TypeScript的类型系统会推断出参数类型,因为函数直接赋值给了 SearchFunc类型变量。 函数的返回值类型是通过其返回值推断出来的(此例是 false和true)。 如果让这个函数返回数字或字符串,类型检查器会警告我们函数的返回值类型与SearchFunc接口中的定义不匹配。

let mySearch: SearchFunc;

mySearch = function(src, sub) {

let result = src.search(sub);

return result > -1;

}

实现接口

与C#或Java里接口的基本作用一样,TypeScript也能够用它来明确的强制一个类去符合某种契约。

interface ClockInterface {

currentTime: Date;

}

class Clock implements ClockInterface {

currentTime: Date;

constructor(h: number, m: number) { }

}

你也可以在接口中描述一个方法,在类里实现它,如同下面的setTime方法一样:

interface ClockInterface {

currentTime: Date;

setTime(d: Date);

}

class Clock implements ClockInterface {

currentTime: Date;

setTime(d: Date) {

this.currentTime = d;

}

constructor(h: number, m: number) { }

}

接口描述了类的公共部分,而不是公共和私有两部分。 它不会帮你检查类是否具有某些私有成员。

继承接口

和类一样,接口也可以相互继承。 这让我们能够从一个接口里复制成员到另一个接口里,可以更灵活地将接口分割到可重用的模块里。

interface Shape {

color: string;

}

interface Square extends Shape {

sideLength: number;

}

let square = <Square>{};

square.color = "blue";

square.sideLength = 10;

一个接口可以继承多个接口,创建出多个接口的合成接口。

interface Shape {

color: string;

}

interface PenStroke {

penWidth: number;

}

interface Square extends Shape, PenStroke {

sideLength: number;

}

let square = <Square>{};

square.color = "blue";

square.sideLength = 10;

square.penWidth = 5.0;

类

类介绍

传统的JavaScript程序使用函数和基于原型的继承来创建可重用的组件,但对于熟悉使用面向对象方式的程序员来讲就有些棘手,因为他们用的是基于类的继承并且对象是由类构建出来的。 从ECMAScript 2015,也就是ECMAScript 6开始,JavaScript程序员将能够使用基于类的面向对象的方式。

使用TypeScript,我们允许开发者现在就使用这些特性,并且编译后的JavaScript可以在所有主流浏览器和平台上运行,而不需要等到下个JavaScript版本。

类

下面看一个使用类的例子:

class Greeter {

greeting: string;

constructor(message: string) {

this.greeting = message;

}

greet() {

return "Hello, " + this.greeting;

}

}

let greeter = new Greeter("world");

如果你使用过C#或Java,你会对这种语法非常熟悉。 我们声明一个 Greeter类。这个类有3个成员:一个叫做 greeting的属性,一个构造函数和一个 greet方法。

你会注意到,我们在引用任何一个类成员的时候都用了 this。 它表示我们访问的是类的成员。

最后一行,我们使用 new 构造了 Greeter类的一个实例。 它会调用之前定义的构造函数,创建一个Greeter类型的新对象,并执行构造函数初始化它。

继承

在TypeScript里,我们可以使用常用的面向对象模式。 基于类的程序设计中一种最基本的模式是允许使用继承来扩展现有的类。

看下面的例子:

class Animal {

move(distanceInMeters: number = 0) {

console.log(`Animal moved ${distanceInMeters}m.`);

}

}

class Dog extends Animal {

bark() {

console.log('Woof! Woof!');

}

}

const dog = new Dog();

dog.bark();

dog.move(10);

dog.bark();

这个例子展示了最基本的继承:类从基类中继承了属性和方法。 这里, Dog是一个 派生类,它派生自Animal 基类,通过 extends关键字。 派生类通常被称作 子类,基类通常被称作 超类。

因为 Dog继承了 Animal的功能,因此我们可以创建一个 Dog的实例,它能够 bark() 和 move()。

下面我们来看个更加复杂的例子。

class Animal {

name: string;

constructor(theName: string) { this.name = theName; }

move(distanceInMeters: number = 0) {

console.log(`${this.name} moved ${distanceInMeters}m.`);

}

}

class Snake extends Animal {

constructor(name: string) { super(name); }

move(distanceInMeters = 5) {

console.log("Slithering...");

super.move(distanceInMeters);

}

}

class Horse extends Animal {

constructor(name: string) { super(name); }

move(distanceInMeters = 45) {

console.log("Galloping...");

super.move(distanceInMeters);

}

}

let sam = new Snake("Sammy the Python");

let tom: Animal = new Horse("Tommy the Palomino");

sam.move();

tom.move(34);

这个例子展示了一些上面没有提到的特性。 这一次,我们使用 extends关键字创建了 Animal的两个子类: Horse 和 Snake。

与前一个例子的不同点是,派生类包含了一个构造函数,它必须调用 super(),它会执行基类的构造函数。 而且,在构造函数里访问 this的属性之前,我们 一定要调用 super()。 这个是TypeScript强制执行的一条重要规则。

这个例子演示了如何在子类里可以重写父类的方法。 Snake类和 Horse类都创建了 move方法,它们重写了从 Animal继承来的 move方法,使得 move方法根据不同的类而具有不同的功能。 注意,即使tom被声明为 Animal类型,但因为它的值是 Horse,调用 tom.move(34)时,它会调用 Horse里重写的方法:

Slithering...

Sammy the Python moved 5m.

Galloping...

Tommy the Palomino moved 34m.

公共,私有与受保护的修饰符

public

在TypeScript里,成员都默认为 public。

你也可以明确的将一个成员标记成 public。 我们可以用下面的方式来重写 Animal类:

class Animal {

public name: string;

public constructor(theName: string) { this.name = theName; }

public move(distanceInMeters: number) {

console.log(`${this.name} moved ${distanceInMeters}m.`);

}

}

private

当成员被标记成 private时,它就不能在声明它的类的外部访问。比如:

class Animal {

private name: string;

constructor(theName: string) { this.name = theName; }

}

new Animal("Cat").name; // 错误: 'name' 是私有的.

protected

protected修饰符与 private修饰符的行为很相似,但有一点不同, protected成员在派生类中仍然可以访问。例如:

class Person {

protected name: string;

constructor(name: string) { this.name = name; }

}

class Employee extends Person {

private department: string;

constructor(name: string, department: string) {

super(name)

this.department = department;

}

public getElevatorPitch() {

return `Hello, my name is ${this.name} and I work in ${this.department}.`;

}

}

let howard = new Employee("Howard", "Sales");

console.log(howard.getElevatorPitch());

console.log(howard.name); // 错误

注意,我们不能在 Person类外使用 name,但是我们仍然可以通过 Employee类的实例方法访问,因为 Employee是由 Person派生而来的。

构造函数也可以被标记成 protected。 这意味着这个类不能在包含它的类外被实例化,但是能被继承。比如,

class Person {

protected name: string;

protected constructor(theName: string) { this.name = theName; }

}

// Employee 能够继承 Person

class Employee extends Person {

private department: string;

constructor(name: string, department: string) {

super(name);

this.department = department;

}

public getElevatorPitch() {

return `Hello, my name is ${this.name} and I work in ${this.department}.`;

}

}

let howard = new Employee("Howard", "Sales");

let john = new Person("John"); // 错误: 'Person' 的构造函数是被保护的.

readonly修饰符

你可以使用 readonly关键字将属性设置为只读的。 只读属性必须在声明时或构造函数里被初始化。

class Octopus {

readonly name: string;

readonly numberOfLegs: number = 8;

constructor (theName: string) {

this.name = theName;

}

}

let dad = new Octopus("Man with the 8 strong legs");

dad.name = "Man with the 3-piece suit"; // 错误! name 是只读的.

参数属性

在上面的例子中,我们不得不定义一个受保护的成员 name和一个构造函数参数 theName在 Person类里,并且立刻给 name和 theName赋值。 这种情况经常会遇到。 参数属性可以方便地让我们在一个地方定义并初始化一个成员。 下面的例子是对之前 Animal类的修改版,使用了参数属性:

class Animal {

constructor(private name: string) { }

move(distanceInMeters: number) {

console.log(`${this.name} moved ${distanceInMeters}m.`);

}

}

注意看我们是如何舍弃了 theName,仅在构造函数里使用 private name: string参数来创建和初始化 name成员。 我们把声明和赋值合并至一处。

参数属性通过给构造函数参数添加一个访问限定符来声明。 使用 private限定一个参数属性会声明并初始化一个私有成员;对于 public和 protected来说也是一样。

存取器

TypeScript支持通过getters/setters来截取对对象成员的访问。 它能帮助你有效的控制对对象成员的访问。

下面来看如何把一个简单的类改写成使用 get和 set。 首先,我们从一个没有使用存取器的例子开始。

class Employee {

fullName: string;

}

let employee = new Employee();

employee.fullName = "Bob Smith";

if (employee.fullName) {

console.log(employee.fullName);

}

我们可以随意的设置 fullName,这是非常方便的,但是这也可能会带来麻烦。

下面这个版本里,我们先检查用户密码是否正确,然后再允许其修改员工信息。 我们把对 fullName的直接访问改成了可以检查密码的 set方法。 我们也加了一个 get方法,让上面的例子仍然可以工作。

let passcode = "secret passcode";

class Employee {

private _fullName: string;

get fullName(): string {

return this._fullName;

}

set fullName(newName: string) {

if (passcode && passcode == "secret passcode") {

this._fullName = newName;

}

else {

console.log("Error: Unauthorized update of employee!");

}

}

}

let employee = new Employee();

employee.fullName = "Bob Smith";

if (employee.fullName) {

alert(employee.fullName);

}

我们可以修改一下密码,来验证一下存取器是否是工作的。当密码不对时,会提示我们没有权限去修改员工。

对于存取器有下面几点需要注意的:

首先,存取器要求你将编译器设置为输出ECMAScript 5或更高。 不支持降级到ECMAScript 3。 其次,只带有 get不带有 set的存取器自动被推断为 readonly。 这在从代码生成 .d.ts文件时是有帮助的,因为利用这个属性的用户会看到不允许够改变它的值。

静态属性

到目前为止,我们只讨论了类的实例成员,那些仅当类被实例化的时候才会被初始化的属性。 我们也可以创建类的静态成员,这些属性存在于类本身上面而不是类的实例上。 在这个例子里,我们使用static定义 origin,因为它是所有网格都会用到的属性。 每个实例想要访问这个属性的时候,都要在 origin前面加上类名。 如同在实例属性上使用 this.前缀来访问属性一样,这里我们使用 Grid.来访问静态属性。

class Grid {

static origin = {x: 0, y: 0};

calculateDistanceFromOrigin(point: {x: number; y: number;}) {

let xDist = (point.x - Grid.origin.x);

let yDist = (point.y - Grid.origin.y);

return Math.sqrt(xDist * xDist + yDist * yDist) / this.scale;

}

constructor (public scale: number) { }

}

let grid1 = new Grid(1.0); // 1x scale

let grid2 = new Grid(5.0); // 5x scale

console.log(grid1.calculateDistanceFromOrigin({x: 10, y: 10}));

console.log(grid2.calculateDistanceFromOrigin({x: 10, y: 10}));

抽象类

抽象类做为其它派生类的基类使用。 它们一般不会直接被实例化。 不同于接口,抽象类可以包含成员的实现细节。 abstract关键字是用于定义抽象类和在抽象类内部定义抽象方法。

abstract class Animal {

abstract makeSound(): void;

move(): void {

console.log('roaming the earch...');

}

}

抽象类中的抽象方法不包含具体实现并且必须在派生类中实现。 抽象方法的语法与接口方法相似。 两者都是定义方法签名但不包含方法体。 然而,抽象方法必须包含 abstract关键字并且可以包含访问修饰符。

abstract class Department {

constructor(public name: string) {

}

printName(): void {

console.log('Department name: ' + this.name);

}

abstract printMeeting(): void; // 必须在派生类中实现

}

class AccountingDepartment extends Department {

constructor() {

super('Accounting and Auditing'); // 在派生类的构造函数中必须调用 super()

}

printMeeting(): void {

console.log('The Accounting Department meets each Monday at 10am.');

}

generateReports(): void {

console.log('Generating accounting reports...');

}

}

let department: Department; // 允许创建一个对抽象类型的引用

department = new Department(); // 错误: 不能创建一个抽象类的实例

department = new AccountingDepartment(); // 允许对一个抽象子类进行实例化和赋值

department.printName();

department.printMeeting();

department.generateReports(); // 错误: 方法在声明的抽象类中不存在

泛型

泛型介绍

软件工程中,我们不仅要创建一致的定义良好的API,同时也要考虑可重用性。 组件不仅能够支持当前的数据类型,同时也能支持未来的数据类型,这在创建大型系统时为你提供了十分灵活的功能。

在像C#和Java这样的语言中,可以使用泛型来创建可重用的组件,一个组件可以支持多种类型的数据。 这样用户就可以以自己的数据类型来使用组件。

非泛型例子

下面来创建 identity函数。 这个函数会返回任何传入它的值。 你可以把这个函数当成是 echo命令。

非泛型例子1:

function identity(arg: number): number {

return arg;

}

非泛型例子2: 使用any类型来定义函数

function identity(arg: any): any {

return arg;

}

使用any类型会导致这个函数可以接收任何类型的arg参数,这样就丢失了一些信息:传入的类型与返回的类型应该是相同的。如果我们传入一个数字,我们只知道任何类型的值都有可能被返回。

泛型的例子

我们需要一种方法使返回值的类型与传入参数的类型是相同的。 这里,我们使用了 类型变量,它是一种特殊的变量,只用于表示类型而不是值。

function identity<T>(arg: T): T {

return arg;

}

我们给identity添加了类型变量T。 T帮助我们捕获用户传入的类型(比如:number),之后我们就可以使用这个类型。 之后我们再次使用了 T当做返回值类型。现在我们可以知道参数类型与返回值类型是相同的了。 这允许我们跟踪函数里使用的类型的信息。

我们把这个版本的identity函数叫做泛型,因为它可以适用于多个类型。 不同于使用 any,它不会丢失信息,像第一个例子那像保持准确性,传入数值类型并返回数值类型。

泛型类

泛型类看上去与泛型接口差不多。 泛型类使用( <>)括起泛型类型,跟在类名后面。

class GenericNumber<T> {

zeroValue: T;

add: (x: T, y: T) => T;

}

let myGenericNumber = new GenericNumber<number>();

myGenericNumber.zeroValue = 0;

myGenericNumber.add = function(x, y) { return x + y; };

GenericNumber类的使用是十分直观的,并且你可能已经注意到了,没有什么去限制它只能使用number类型。 也可以使用字符串或其它更复杂的类型。

let stringNumeric = new GenericNumber<string>();

stringNumeric.zeroValue = "";

stringNumeric.add = function(x, y) { return x + y; };

console.log(stringNumeric.add(stringNumeric.zeroValue, "test"));

与接口一样,直接把泛型类型放在类后面,可以帮助我们确认类的所有属性都在使用相同的类型。

我们在类那节说过,类有两部分:静态部分和实例部分。 泛型类指的是实例部分的类型,所以类的静态属性不能使用这个泛型类型。

枚举

默认情况下,枚举是基于 0 的,也就是说第一个值是 0,后面的值依次递增。不要担心,当中的每一个值都可以显式指定,只要不出现重复即可,没有被显式指定的值,都会在前一个值的基础上递增。

enum Color {Red, Green, Blue}

let c: Color = Color.Green; // 1

或者

enum Color {Red = 1, Green, Blue = 4}

let c: Color = Color.Green; // 2

枚举有一个很方便的特性,就是您也可以向枚举传递一个数值,然后获取它对应的名称值。举个例子,如果我们有一个值 2,但是不清楚在 Color 枚举中与之对应的名称是什么,我们就可以通过以下的方式来进行检索:

enum Color {Red = 1, Green, Blue}

let colorName: string = Color[2]; // 'Green'

但是像上面的这种写法不是太好,因为如果您给定的数值没有与之对应的枚举项,那么结果就是 undefined。所以,如果您想要得到指定枚举项的字符串名称,可以使用类似这样的写法:

let colorName: string = Color[Color.Green]; // 'Green'

命名空间

TypeScript里使用命名空间(之前叫做“内部模块”)来组织你的代码。任何使用 module关键字来声明一个内部模块的地方都应该使用namespace关键字来替换。 这就避免了让新的使用者被相似的名称所迷惑。

命名空间介绍

下面的例子里,把所有与验证器相关的类型都放到一个叫做Validation的命名空间里。 因为我们想让这些接口和类在命名空间之外也是可访问的,所以需要使用 export。 相反的,变量 lettersRegexp和numberRegexp是实现的细节,不需要导出,因此它们在命名空间外是不能访问的。 在文件末尾的测试代码里,由于是在命名空间之外访问,因此需要限定类型的名称,比如 Validation.LettersOnlyValidator。

namespace Validation {

export interface StringValidator {

isAcceptable(s: string): boolean;

}

const lettersRegexp = /^[A-Za-z]+$/;

const numberRegexp = /^[0-9]+$/;

export class LettersOnlyValidator implements StringValidator {

isAcceptable(s: string) {

return lettersRegexp.test(s);

}

}

export class ZipCodeValidator implements StringValidator {

isAcceptable(s: string) {

return s.length === 5 && numberRegexp.test(s);

}

}

}

// Some samples to try

let strings = ["Hello", "98052", "101"];

// Validators to use

let validators: { [s: string]: Validation.StringValidator; } = {};

validators["ZIP code"] = new Validation.ZipCodeValidator();

validators["Letters only"] = new Validation.LettersOnlyValidator();

// Show whether each string passed each validator

for (let s of strings) {

for (let name in validators) {

console.log(`"${ s }" - ${ validators[name].isAcceptable(s) ? "matches" : "does not match" } ${ name }`);

}

}

Comments